Many organizations face the complex dilemma of dealing with major strategic and operational changes, often simultaneously. The complexity of the management challenge is increasing, often with alarming speed and consequences. This causes, not just a superabundance of operational problems, but strategic hazards that may test the viability of the organization. Key macro-challenges might include:

Many organizations face the complex dilemma of dealing with major strategic and operational changes, often simultaneously. The complexity of the management challenge is increasing, often with alarming speed and consequences. This causes, not just a superabundance of operational problems, but strategic hazards that may test the viability of the organization. Key macro-challenges might include:- radically increased customer expectations

- sector and business-model disruption

- reducing costs of market entry

- intensified competition

- radically and rapidly changing technology

- cost pressures

- mounting regulatory-compliance demands

- diminishing staff numbers

- increasing operational complexity

- fragile workforce enthusiasm

These are mission-critical problems and there is a growing realization that something new is needed if they are to be solved.

The organization chart shapes traditional management. Management effort consequently focuses on functional areas, i.e. ‘boxes on the chart’, and is easily fragmented. This form of ‘functional’ management has always been a key feature of management practice. Long before the invention of the theory of contemporary management in the first half of the twentieth century, organizations have structured themselves into units based on the type of work performed.

Just as clearly, to get work done, to deliver value (products and services) to customers, requires collaboration across the organization and coordinated work across the separate functional areas. Every organization creates, accumulates, and delivers value across its organizational structure. Resources are managed ‘vertically’, following the organization chart, but the value pathway is ‘horizontal’, based on cross-functional collaboration.

To take a familiar example, imagine the sequence involved in air travel. The passenger arrives, checks in, boards the plane, completes the flight, retrieves luggage, and leaves the airport. For the passenger to have a good trip, all of that must go well. No point having the world’s best check-in service if the luggage is lost. Having to find lost luggage is both annoying for the passenger and expensive for the airline.

The creation, accumulation, and delivery of value to customers is inherently cross-functional and requires collaboration across the organization, and often beyond into other organizations. This is fact, not an opinion to challenge or a point of view to contest. Management needs its own disruption, a radical departure from the traditional model.

Organizations must be good at identifying circumstances that threaten performance, but that is not enough. They also need to look for characteristics that make it strong, and for opportunities to do something new, perhaps radically innovative.

It is no longer enough, if it ever was, to focus on immediate performance issues and ignore opportunities for improvement. Henry Ford reduced the build-time for a Model T chassis from 12½ to 1½ hours—a prodigious feat, an innovation whose impact is still felt today, but it would have been pointless if no one wanted to buy a car.

In 1976, with a ninety per cent share of the US market, Eastman Kodak was ubiquitous; by the late 1990s it was struggling; by 2012 it was in bankruptcy protection. Despite having invented the digital camera in 1975, Kodak was slow to react to a serious decline in photographic film sales. At its peak, Kodak also had a great story to tell about increasing efficiency and performance improvement. It became efficient at producing a product few wanted, and good at delivering services few needed.

In times where digital substitutes overwhelm established business models, every organization must expect to have its own ‘Kodak moment’.

The primacy of process

A business process is a collection of activities that transforms one or more inputs into one or more outputs. Many resources are involved in the management and execution of a process—customers, staff, materials, systems, infrastructure, information, technology, suppliers, facilities, policies, regulations—and these must also be seen to be integral to the definition of process. Processes are vital because this is how organizations get work done.

The fundamental concept underpinning the ideas and practices described in this paper is the primacy of process. This says that business processes are the only way any organization can deliver value to customers and other stakeholders outside the organization. By themselves, the separate functional areas of an organization cannot deliver value to external parties. It follows that every organization executes its strategic intent via its business processes.

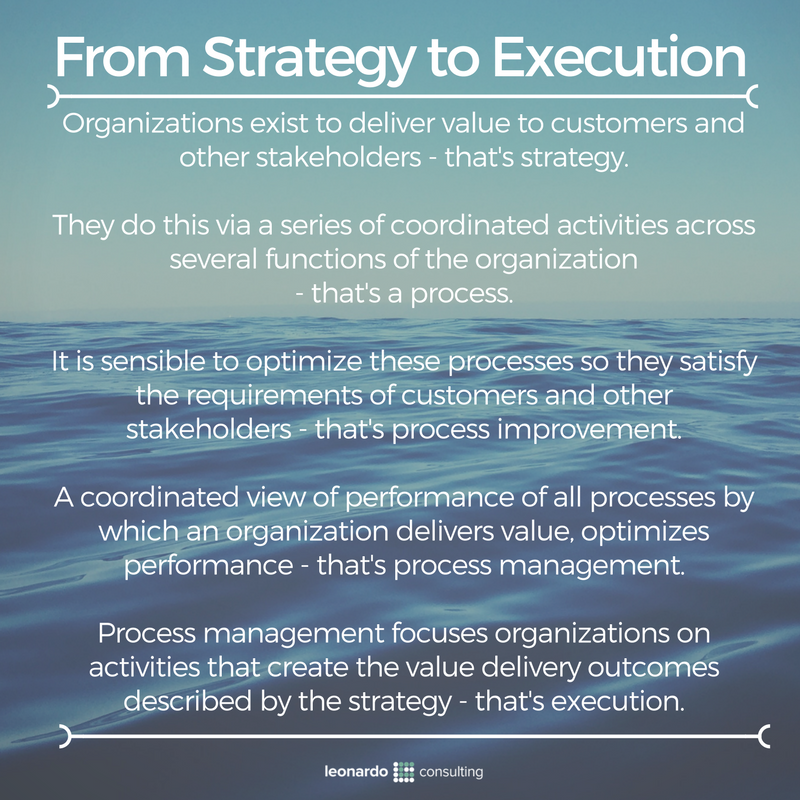

The sequence from strategy to execution is shown in Figure 1, encapsulating both the strategic and the operational importance of the process view.

The inescapable conclusion is that the starting point for effective organizational management is to understand, manage, and optimize those business processes. Without a proactive focus on business processes, organizational performance cannot improve and strategy cannot be effectively executed.

- If value is created, accumulated, and delivered across the organization, are those value pathways defined and documented?

- If value is created, accumulated, and delivered across the organization, what measures of performance are made in that direction?

- If value is created, accumulated, and delivered across the organization, who is in charge of that?

Organizations must reimagine their operations as value creation and delivery flows that must be proactively managed and continually improved. The management philosophy that facilitates that is process-based management.

Defining process-based management

Bringing together these concepts, three principles underpin process-based management:

1. Business processes are the collections of cross-functional activities that deliver value to an organization’s external customers and other stakeholders—the only way that any organization can deliver such value. Individual functional areas cannot, by them-selves, deliver value to external customers.

2. It follows that an organization executes its strategic intent via its business processes. Business processes are the conduits through which value is exchanged between customers and the organization. Therefore, business processes need to be thought-fully managed and continuously improved to maintain an unimpeded flow of value with customers and other stakeholders.

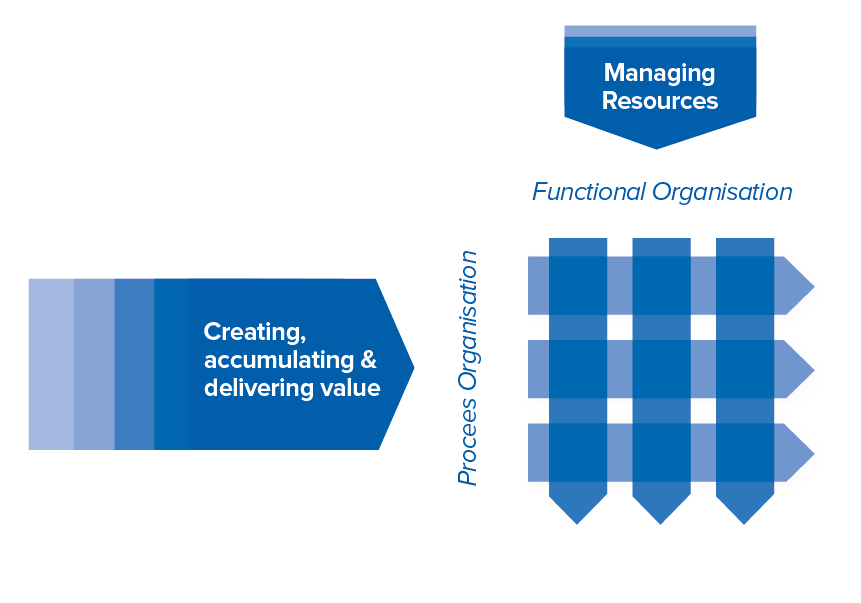

3. An organization’s resources are traditionally managed vertically via the organization chart. Value is created, accumulated, and delivered horizontally across that chart. Value is accumulated, not up and down the functions as represented in an organization chart, but across the organization as shown in a business process architecture. The various functions collaborate via business processes to create, accumulate, and deliver value to customers and other stakeholders in the form of a desired product, service, or some other outcome.

Figure 2: Functional and process organization views

The profound premise for process-based management is illustrated in Figure 2, showing both the functional and process organizational views.

Enabling process-based management

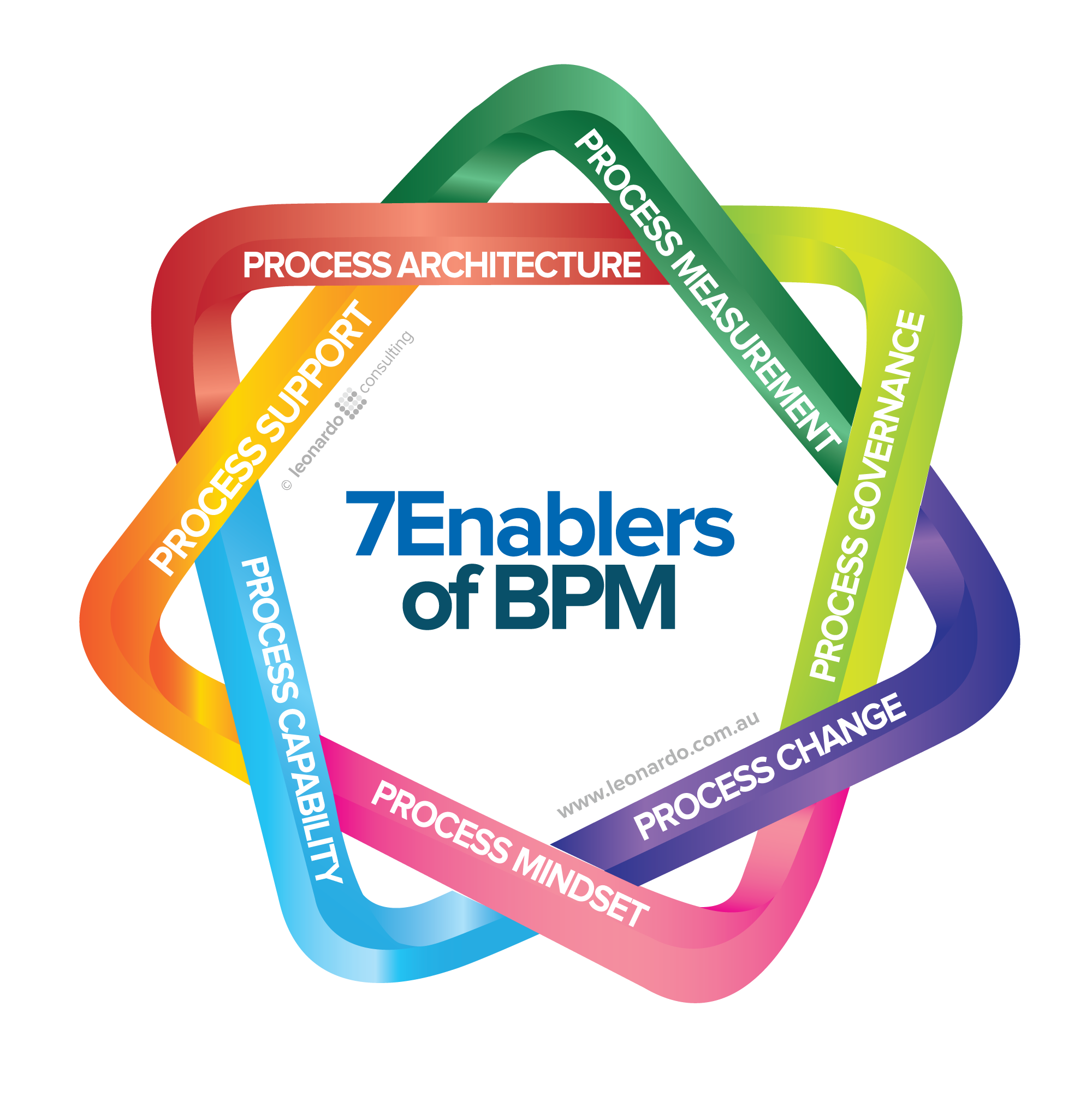

Seven elements, the 7Enablers of BPM, come together to create and sustain process-based management. If developed simultaneously at the pace appropriate to the organization, these elements significantly increase the likelihood of creating sustained process-based management.

The 7Enablers is a collective of mutually supportive prerequisites for successful and sustained process-based management.

- Process architecture: discovery, understanding, and documentation of the organization’s business processes and related resources in a hierarchical model.

- Process measurement: defining process performance measures and measurement methods, collecting and reporting process performance data.

- Process governance: reimagining, and responding to, process performance anomalies, innovation opportunities, process documentation, and general hygiene.

- Process change: continually discovering ways to close process performance gaps by eliminating problems and capitalizing on opportunities.

- Process mindset: creating an environment where the organization, its people, and their teams, are always conscious of the processes in which they participate.

- Process capability: developing the tools and skills required throughout the organization to identify, analyze, improve, innovate, and manage business processes.

- Process support: providing support throughout the organization to develop, sustain, and realize process-based management benefits.

Figure 3: The 7Enablers of BPM

These seven enablers are shown in Figure 3. A Mobius strip format is used to highlight the interdependencies between the elements.

To thrive, perhaps even to survive, in times when ‘doing more with less’ seems both inevitable and impossible, executives need to reimagine their organizations as value-creation and delivery flows. Process-based management delivers a practical, proven approach and the 7Enablers represents a breakthrough in management practice.

Managing reimagination

This paper has discussed seven enablers of process-based management, seven elements that will put management focus where it should be, on cross-functional value creation, accumulation, and delivery. If you accept the premise that no unit identified on an organization chart can, by itself, deliver value to an external customer or other stakeholder, (and how could you not do so?) then you accept the main concept of process-based management. The inevitable consequence of that is acceptance of the certainty that processes must be identified, analyzed, improved and managed. Since the organization chart is silent on the management of cross-functional processes, a separate, targeted, and comprehensive intervention is required to enable process-based management and realize the benefits that come from it.

At a time when the requirement to ‘do more with less’ seems both inevitable and impossible, process-based management delivers a practical, proven approach.

This article is an edited extract from the book, Reimagining Management. From the foreword by Professor Michael Rosemann: ‘This book has the potential to become an essential, shared point of reference for designing organizations.’