A Process By Any Other Name....

“What’s in a name? That which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet.”

William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, Act II, Scene I

What’s in a name? Not so much? What is important is what we mean and understand by the thing that is named. Shared understanding is everything; without understanding, there is no effective communication. If we begin with unknown differences in the way we visualize and name basic concepts, there is no way we can converge on common understandings and develop sophisticated models of how the world works. Without understanding, we can’t even have rational conversations about our different views.

While the nature of an object is more important than what we call it, language can be a powerful force for understanding, as well as for misunderstanding. When it comes to gaining a shared understanding in BPM and related areas, we are too often ‘separated by a common language’.

In the general discourse around business processes and their modeling, management, and improvement, we have a problem with the conflicted use of process language. When we start conversations about business process theory and practice with fundamental differences in the conceptualization of the idea of ‘process’, it’s not going to end well. The problem is that we can have very different ideas about what a process is, and these differences can exist in every language. It’s much more fundamental than us saying inkqubo, فرآيند, processus, quy trình, proceso, proces, inshila, próiseas, اجراء عمل, prozess, mchakato, prosess, processo, inqubo, prosessi, प्रक्रिया, or process.

The process problem

I hear processes called all sorts of things: business process, capability, process area, value chain, process group, business service, component, value stream, machine, service, responsibility, procedure—and there are, no doubt, many more. Now, I can hear lots of people saying “No! Such-and-such is not a process.” But that’s the problem; we all think we are correct, and anyone who disagrees with us is misguided. Don’t you agree!?

It’s often more than just having different names for processes; we start from different fundamental assumptions about what the term should describe.

Differences in the definition of basic concepts in and around BPM are not just of pedantic or pedagogic interest. They cause a lot of wasted time and create confusion, which handicaps development. To illustrate the point, there have been several long discussions about ‘process’ vs. ‘capabilities’ in various LinkedIn discussion groups. One that I followed for a while continued for over 12 months and, last time I looked, had gone through the 300 comments mark—and it’s mainly people talking at cross purposes because of different definitions of the fundamentals. A new LinkedIn discussion about the meaning of ‘value chain’ is showing all the signs of another long and circular run.In some cases, it’s not as hard-edged as that, and the various terms are suggested as being ‘sort of the same’. That doesn’t help. If a component or capability or machine is much the same as a process, then why do we need more than one term? Choose whichever term you prefer, but let’s document an architecture, not a thesaurus.

Does it help to call ‘processes’ at the different levels of a hierarchy by different names? Does a process that is reused throughout an organization need to be called something other than a process? Adjectives are useful. Couldn’t it be a level 1 process and a common process? Do we solve the problem of not knowing what a process is by inventing an additional name we don’t understand?

It’s often more than just having different names for processes; we start from different fundamental assumptions about what the term should describe. Starting from different perceptions, we inevitably end up in different places, and we waste a lot of time arguing about the relative benefits of unreal differences.

Where it all begins

Having thought about this for a long time, and participated enthusiastically in many of the pointless arguments caused by an unnoticed lack of agreement at the most basic level, I have finally discovered that the reason for the dissonance is quite simple—perhaps embarrassingly so.

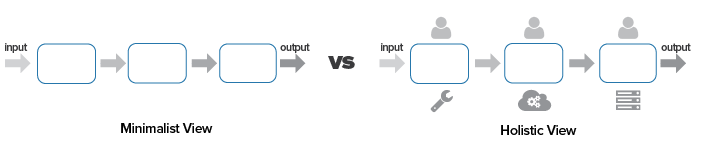

You might think of a process as a set of related activities, with definite triggers and results, that transforms inputs into outputs. Essentially, this is visualized as a set of boxes and arrows in a process model. I call this the minimalist view.

Alternatively, you might think of a process as everything described above, plus all that is needed to execute and manage the process—that is, all of the resources, systems and people. I call this the holistic view.

When you start with the minimalist view, you fairly soon decide that there is something missing, namely all of the resources, systems, and people required to execute and manage the process—that is, all the additional elements included in the holistic view. If a process is just a series of activities, you need to find something else that will do the rest of what is required. Hence, we create new concepts like capabilities, components, machines, etc. When you start with the holistic view, there is nothing missing.

When some folks start with the holistic view and some with the minimalist view, it’s not surprising we have disagreements. I’m not saying either is definitively correct; the world could operate with either. However, the problem is we are trying to operate with both, and without being conscious that we are doing so.

Modeling the problem?

Might it be that the problem is, I won’t say caused, but exacerbated by having a heavy emphasis on process modeling, particularly modeling of an uncomplicated nature that focuses on just capturing activity sequences? Our view of what comprises a process might easily be shaped, or at least influenced, by the visualizations of them with which we are familiar. ‘Process’ might naturally be conflated with ‘process model’. If you start by seeing processes represented only as boxes and arrows, that is likely to nurture the minimalist view where you perceive a process as a type of documentation. If your experience is that processes are represented by a modeling database rich in information about activities, people, systems, data, performance, and other interrelationships, it will be hard to take anything other than the holistic view, and the idea of ‘process’ becomes much more than documentation—it becomes a proactive management tool.

A corollary of this would be that your position on the holistic-minimalist scale might be influenced by the modeling tools you use. Although it doesn’t have to be like this, a modeling tool that is essentially a drawing package is likely to be used to draw minimalist process representations, and a more sophisticated repository-based tool lends itself to a more complex view of a process. Of course, we can’t blame the tool. At most, this can be just one element of what forms our personal ‘process view’.

Our exposure to visualizations of process must have a strong effect on our perceptions of process. While it can’t be the whole story—and there is nothing inevitable about the various experience pathways—modeling processes must inevitably influence the modeling of our process view.

Does this matter?

So, does all this matter? Is there a problem, an impact that should worry us? Yes, I think there is.

It’s not the issue of which word you use to describe a ‘process’. While I find ‘process’ a perfectly good word that does not need to be reinvented or supported by other nouns, there should not be a problem in using other words (assuming shared understanding and consistent use) except in communicating with people, perhaps outside your organization, who use a different language. I recently worked in an organization where ‘holistic processes’ are called ‘machines’, and I came to find that term quite compelling in that environment.

If you want to test the extent of the problem and its possible impacts, listen to the conversations around you about ‘process’ and note the various terms used. Then ask a selection of colleagues to write down their personal understanding of what each of those terms mean. Test those written responses against what you hear people say, and get the respondents together to discuss the differences.

The problem is that poor definition of terms, inconsistent usage, unnecessary complexity, and general fuzziness about the nature of a business process, leads to pointless arguments, confusion, and the significant opportunity cost of not working to a shared ‘theory of process’ that is integrated, coherent, scalable, and fractal.

I think the holistic definition of a process is the most effective approach. It simplifies the process view and removes the need the additional complexity to compensate for the minimalist perspective. It allows for a much richer discussion about how organizations create, accumulate, and deliver value to their customers and other stakeholders.

What can we do?

While it would be good to imagine that throughout the ‘world of process’ we might come to some common agreement about the nature of a process, that’s not going to happen. The practical target we can set is that in each organization we take steps to be as clear as possible in the language used—not just in what we say, but also in how we think about processes.

The general strategy must be to use clean language with a minimum vocabulary that is understood and utilized by all. Here are five ProcessTalk practices that can achieve those objectives.

- Clean it up. The language of process must be well defined with clear meanings for each word in the vocabulary without fuzzy edges and unresolved overlaps. Seek out and remove any confusion in the way process issues are discussed.

- Keep it short. The process vocabulary should be as brief as possible and as long as it needs to be. Synonyms, real or imagined, are not required. A single term like process (or widget, or whatever you prefer) can, with appropriate adjectives, be used to describe every hierarchical level and every variation.

- Write it down. Document the process vocabulary; create the glossary of terms, and describe in as much detail as is useful about how each term is used.

- Share it. Actively ensure that everyone understands the language of process. Make it available, explain it, talk about it—bring it to life so that it will be used.

- Speak up. Insist that the correct language is used and, when it isn’t, speak up and ask for clarification. Create the habit of using the right language in the correct context.

Business process management (or, better, process-based management) is a management philosophy that requires us to think differently about organizations and how they operate. The cross-functional, or end-to-end, approach is very different for most organizations, their teams, and people.

Clean language used consistently won’t solve every problem in that transformation, but it removes the distractions of unnecessary confusion, improves clarity in thinking and reasoning, and makes it easier to explain the important concepts.

Postscript

I asked a French colleague, Clement Hurpin, to review this article and I thank him for his insights. As an aside, Clement mentioned a personal perspective that I thought was compelling, and I share it with you:

I can relate to this paper in a strange way. I lived in Quebec, where people speak a different French than mine. Some words were the same but used for different things. For example, a ‘camisole’ in Quebec is a sleeveless T-shirt, but in France is a straitjacket! As French citizens living in Quebec, we were advised not to assume that we spoke the same language – ‘you might use the same words, but they have different meanings.’

It seems we are not alone!

The Macquarie Dictionary (the best reference for Australian English usage) says that ‘camisole’ is ‘a woman’s simple top with narrow shoulder straps, now usually worn as an undergarment.’ Prenez garde, Clément!